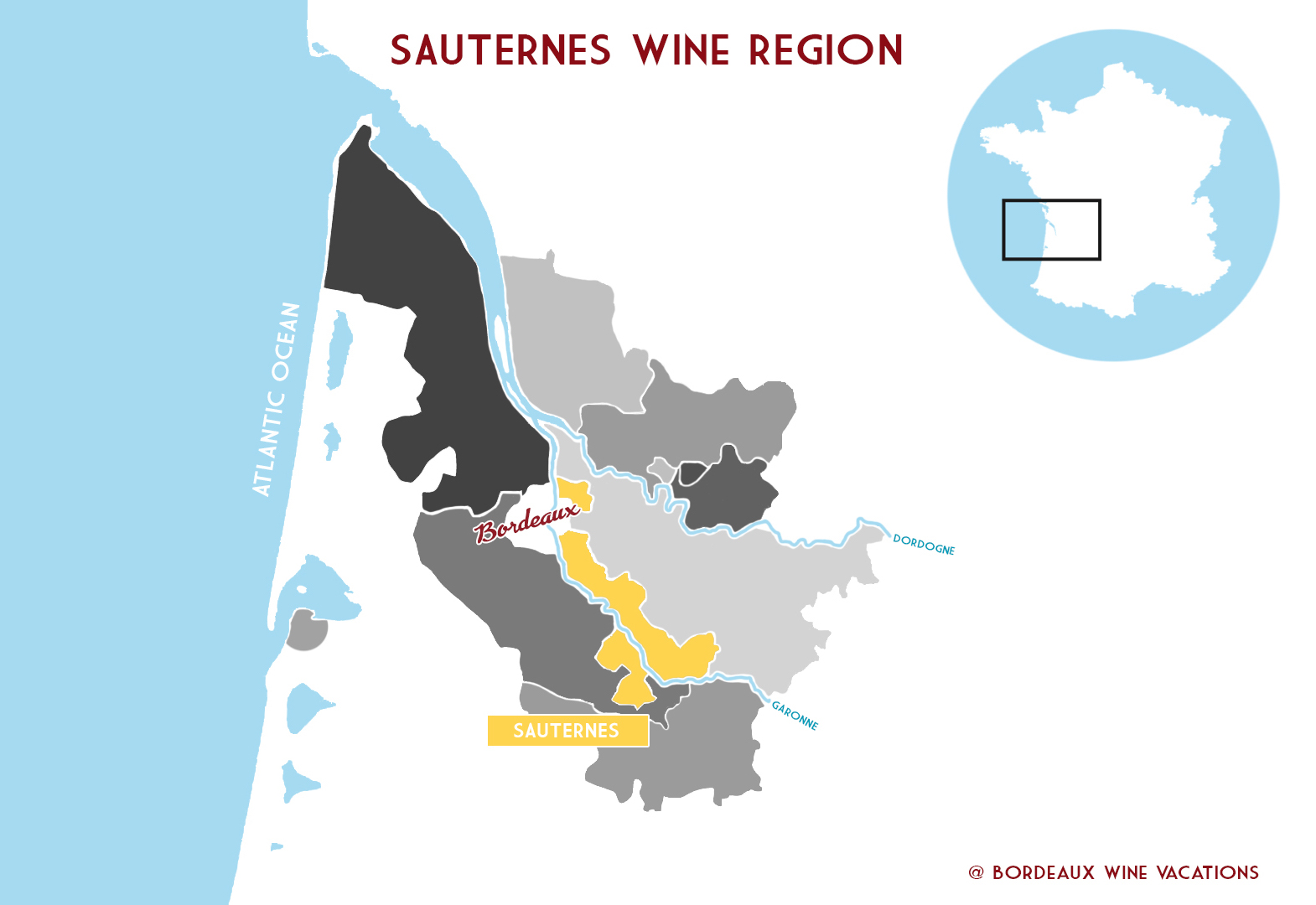

South of Bordeaux, where the Garonne and Ciron rivers meet, the vineyards of Sauternes glow with a light that feels almost otherworldly. It’s one of those places that you can visit a dozen times and still find yourself pausing to take it in, the morning mist hanging low over the vines, the quiet rhythm of a region that’s mastered patience.

This small corner of Bordeaux has built its name on something most winemakers spend their lives trying to avoid: rot. But here, it’s noble rot — Botrytis cinerea — and it’s the secret behind Sauternes’ famous golden wines. When the Ciron’s cool air meets the warmer Garonne, the resulting fog encourages this delicate fungus to form on the grapes. It gently shrivels them, concentrating their sugars and aromas until every drop of juice tastes like honey, apricot, and sunlight.

There’s nothing predictable about making Sauternes. The weather decides everything. Harvest happens berry by berry, over several passes through the vineyard, pickers selecting only the clusters touched just enough by botrytis. It’s slow, meticulous work that can stretch for weeks. But the reward is worth it: wines that balance richness with brightness, sweetness with freshness.

The result isn’t syrupy or cloying; it’s layered and alive. A good Sauternes has texture. It moves across the palate like silk, with flavors of candied orange, almond, acacia, and spice that linger long after the glass is empty. Even those who say they don’t like sweet wines tend to change their minds once they’ve had the real thing here, at the source.

Sauternes’ fame reached its height in the 19th century, when Château d’Yquem was crowned Premier Cru Supérieur in the 1855 Classification — the only estate in Bordeaux ever to hold that title. Even now, Yquem remains a benchmark of perfection: a wine that can age for generations without losing its elegance.

But the story doesn’t stop there. Properties like Château Guiraud, Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey, and Château Suduiraut produce extraordinary wines in their own right, each with its own fingerprint of sweetness, minerality, and finesse. What unites them all is the soil: a mix of limestone, gravel, and clay, and the quiet confidence of those who farm it.

The 20th century brought challenges as tastes shifted toward drier styles, but Sauternes has weathered them gracefully. Many winemakers now produce small quantities of dry white wines alongside their sweet cuvées, a testament to the region’s adaptability and creative spirit.

The classic pairing is foie gras, but locals know Sauternes works beautifully with so much more. Try it with roast chicken, lobster, or blue cheese; it holds its own with savory dishes just as well as with dessert. One of the best matches you’ll ever taste might be a chilled glass of Sauternes with a simple tarte au citron at La Chapelle Restaurant inside Château Guiraud.

And don’t be surprised if your host pours a glass before dinner — around here, a small pour of Sauternes as an apéritif is considered perfectly normal.

A visit here feels different from Bordeaux’s grand red wine regions. It’s slower, quieter, more contemplative. You might start your day at a small family-run château, standing among rows of vines heavy with late-harvest fruit. Your guide explains the rhythm of botrytis, how the pickers know when a grape is ready, and why every year brings something slightly different.

Lunch could be at a first-class estate’s fine-dining restaurant, with dishes that mirror the wines’ balance of richness and lightness.

Then it’s on to the region’s crown jewel, Château d’Yquem, to see where patience and precision have been elevated to an art form.

By late afternoon, as the sun dips low and the vines shimmer in gold, you’ll understand what makes this place special. Sauternes isn’t just about sweetness, it’s about time, trust, and the quiet beauty that comes from letting nature take the lead.